Myron King is selling his collection of mineral and lapidary specimens, and possibly some of his tools. The sale was on July 11, 2015 from 1- 5 pm. Thank you for your interest.

Scepter Quartz

Article by Amir Chossrow Akhavan, http://www.quartzpage.de/gro_text.html

A scepter quartz is often defined as a quartz crystal that has a second generation crystal tip sitting on top of an older first generation crystal. The second generation tip typically becomes larger than the first generation tip, but might also become smaller. A scepter can be shifted sideways and does not need to be centered on the first generation tip.

However, there is a problem with a definition that is based on the idea of a second generation: scepters do not only occur as a second generation on an older crystal, they also form stacks of parallel grown crystals that developed at the same time, very often as skeleton quartz. Another difficult case are reverse scepters in which the scepter is smaller than the underlying tip. Here the smaller tip very often does not show any properties that clearly distinguish it from the rest of the crystal and that would justify calling it a second generation. Instead, the crystals often appear to have grown continuously into the reverse scepter or multiple scepter shape.

In all cases, the scepter develops from the already present crystal lattice of the crystal underneath. Thus, to be a scepter quartz, the “second generation” crystal’s a- and c-axes need to be oriented parallel to the respective axes of the “first generation” crystal; just one crystal on top of another doesn’t make it a scepter. Such a crystallographically well defined intergrowth of different minerals is called an epitaxy. In a sense, a scepter represents an epitaxy of quartz on quartz, and because it is the same mineral, it is sometimes called an autotaxy.

Scepters are quite common in certain geological environments. Amethyst from alpine-type fissures in igneous and highly metamorphosed rocks usually occurs as scepters on top of colorless or smoky crystals (not only in the Alps, but for example also in southern Norway or northern Greece). Here, the amethyst generation grew at lower temperatures than the first generation quartz. The same growth form can be observed in pegmatites and miaroles in igneous rocks (for example, amethyst scepters from the Brandberg, Namibia, or from pegmatites in Minas Gerais, Brazil).

Scepters, or to be precise, the “second generation” part of a scepter quartz that defines it, commonly have a number of morphological properties:

- Scepters are commonly of normal habit and are never tapered. The underlying “first generation” crystal may show a Tessin habit, but the scepter on it will not.

- Scepters tend to assume a short prismatic habit. An apparent exception are reverse scepters and the normal scepters associated with them, which may occur as elongated extensions of a “first generation” crystal, but then in the shape of multiple stacked scepters.

- Many scepters show only a weak striation on their prism faces, sometimes it is even missing.

- Scepters do not show split growth patterns.

- Scepters rarely show trigonal habits with very small or missing z-faces. An exception are reverse scepters and the normal scepters associated with them.

- Scepters are often associated with skeleton growth forms (skeleton or window quartz).

- Scepters commonly show a color, color distribution, diapheny and surface pattern that is markedly different from the underlying “first generation” crystal. Often they are more colorful and transparent. Amethyst scepters are very common, smoky quartz scepters -often with uneven color distribution- are common. An exception are reverse scepters and the normal scepters associated with them which seem to either not differ from the “first generation” or show gradual transitions.

- Summarizing the exceptions above: Reverse scepters and the normal scepters associated with them seem to have a different set of properties.

Formation

One theory is that a scepter forms when crystal growth is interrupted and parts of the crystal are covered with some material that inhibits further growth. The growth inhibiting material might be only present as a very thin layer and invisible. The very tip of the crystal or the entire rhombohedral faces remain free of that material, and should the conditions change again, the crystal continues to grow from the tip.

One of the problems with that theory is that you would expect to see a larger number of “double”, “triple” or “quadruple scepters”, specimen in which the growth had been interrupted several times and in which scepters with slowly changing habits are stacked. In nature, however, you see a strong dominance of “simple” scepters that consist of just a prism with “a single head”. If you see multiple scepters, then often alongside simple scepters, although multiple changes in the environment should have affected the morphology of all of them equally.

Another problem is that you would not expect to see a fully-grown scepter that encloses the former tip like an onion if the crystal simply started growing from a single point on the surface of the tip. Such a crystal would finally grow into an elongated crystal and would at best assume the shape of a reverse scepter.

As I’ve mentioned, amethyst from igneous and metamorphic rock locations all over the world predominantly occurs as scepters. Even if you just take Alpine locations, it is hard to imagine that the environmental conditions in all those locations have undergone a single sudden change that led to a temporary growth inhibition on the crystals, followed by a very distinctive growth pattern, the formation of scepters.

The internal structure of scepters from Alpine-type fissures (and of scepters in general) is perhaps always lamellar, as opposed to the macromosaic structure of many quartz crystals from Alpine-type fissures. Quartz crystals with a macromosaic structure may carry a scepter, but the scepter will then show lamellar structure.

Fossil Sweet Gum

This is a cross-section of a fossilized sweet gum tree from the Hampton Butte in Crook County, Oregon. We saw it at the Rice Museum in Hillsboro, Oregon where it is in the petrified wood room. I hardly ever see petrified wood that is green like this; usually it’s red, orange, or brown. Anybody know what makes it green?

Flowers in an Agate

Photo by Vítězslav Snášel, http://www.mindat.org/article.php/885/Agates+-+hidden+beauty

This pattern in this agate from the Czech Republic looks like pussy willows in the spring. What do you think it looks like?

Corundum

Photo by Greg Slak, http://www.mindat.org/photo-189496.html

Corundum (Al2O3) is a hematite group mineral that has trigonal crystals. It is found all over the world and can be many different colors including blue, red, pink, yellow, gray, and colorless. These corundum crystals are from the Cascade Canyon in San Bernadino, California. They may not look familiar to you, but corundum has some famous relatives. A gem-quality corundum that is red (Cr-bearing) is known as ruby, and a gem-quality corundum that is blue (Fe- and Ti-bearing) is known as sapphire.

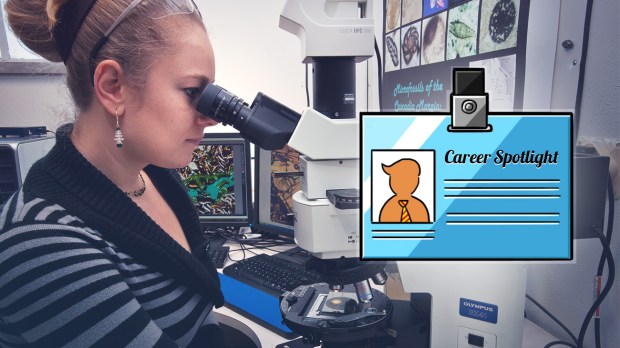

What Does a Research Geologist Do?

An article originally by Andy Orin found on Lifehacker here: http://lifehacker.com/career-spotlight-what-i-do-as-a-research-geologist-1690402642

It’s appealing to think that a geologist spends most of their time scouring remote landscapes with a rock hammer and a magnifying glass, but in reality they spend more time in a laboratory than a Land Rover. The work of a research geologist is eclectic, analytical, and scientific.

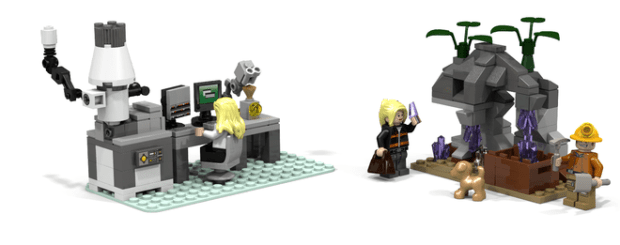

To learn a little about the field, we spoke with Circe Verba, Ph.D., a young researcher at the National Energy Technology Laboratory, and who has previously worked with NASA and SETI. Circe is also involved with science outreach and education with high school students, and has even designed a LEGO set depicting what it’s like to be a geologist. Now let’s take a look through the microscope:

Tell us a little about yourself and your experience.

I am a research geologist at the National Energy Technology Laboratory’s (NETL) Office of Research & Development (ORD). I specialize in bridging geochemistry and civil engineering—specifically projects that involve carbon sequestration and wellbore integrity (relevant to mitigating climate change) and understanding the interaction of oil-gas shale in unconventional systems. My expertise is electron microscopy and image analysis.

What drove you to choose your career path?

I had many inspirations as a child; it started with my earth science class with discovering the planets. I had a thirst for knowledge to understand processes at a macroscopic scale down to a micro-scale. Geology is a multidisciplinary science that spans several fields, such as engineering and research, which enabled me to pursue several interests.

How did you go about getting your job? What kind of education and experience did you need?

I wanted to pursue a career that would expand my perception of the universe by conducting research. I participated in high school science clubs which provided a scholarship opportunity to attend college at Oregon State University. Research (nowadays) requires a Ph.D., which took me long nine years. During my undergraduate, I explored astronomy, oceanography, and geology. I studied microbial boreholes in freshwater pillow basalt for planetary applications. Then I started a geology master’s program at Northern Arizona University, studying Martian aeolian [wind erosion] and volcanic features as part of a NASA HiRISE fellowship. Once that program ended, I switched gears and participated in an Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) post-graduate fellowship in 2009. At NETL I was encouraged to further my education which led to the completion of my Ph.D in 2013, and a permanent job studying engineered systems on Earth.

What kinds of things do you do beyond what most people see? What do you actually spend the majority of your time doing?

My time depends on what stage the project is at—at the moment I have four projects in different stages. I can spend time in the laboratory conducting experiments, analyzing and characterizing samples under an electron or light microscope, or working on the computer drafting manuscripts for publications. I also spend a lot of time interfacing with other team members and key partners from universities. It is also vital for scientists to communicate with one another on their work at scientific conferences.

What misconceptions do people often have about your job?

One misconception is not about my job, but more about the field. A common joke is that geology is rock for jocks, however, geology can be quite complex. In addition, as a geologist you get a lot of random rocks brought to you hoping for special identification when it’s usually a common rock like an agate (quartz-polymorph).

What are your average work hours?

A normal, professional work week—40 hours/week. More if there are deadlines or traveling.

What personal tips and shortcuts have made your job easier?

Spreadsheets are essential for project management to keep track of project tasks or budgets, as well as from a technical stand point to understand chemical analyses and to calculate, graph, and import data.

Another tip is sharing data; part of being a scientist is to not replicate work that has been done or is being conducted. It is then helpful to publish the research or put data onto a database for distribution. We use the Energy Data eXchange (EDX) at NETL.

What do you do differently from your coworkers or peers in the same profession? What do they do instead?

As I said above, I spend more time in the experimental and petrographic laboratory and interpreting the results. I spend less time in the field than my peers, for example, collecting samples, mapping regions, or being on an oil rig. In addition, several of my peers primary focus use applied geophysical modeling or geographic information system (GIS) to capture, store, manage, analyze spatial data. Furthermore, many geologists are in academia, which includes research and teaching.

What’s the worst part of the job and how do you deal with it?

Personally, the worst part of the job is the amount of technical writing required. You undergo a lot of revisions for technical reports and peer reviewed journal articles. I’m a descriptive writer, so I’ve had to learn to reign it in and learn from mistakes.

What’s the most enjoyable part of the job?

The most enjoyable part of the job is when I’m using the microscopes. You get to see details down to a micrometer scale, something the naked eye can’t see. It’s an unseen world that I get to be a part of. It can also be like a micro-treasure hunt to find changes in mineral phases or microorganisms.

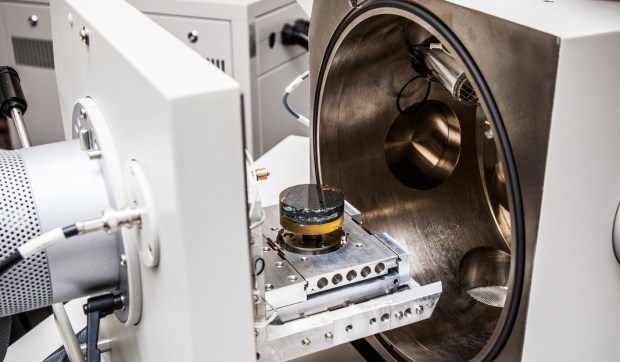

Lab photos from NETL: https://www.flickr.com/photos/netlmultimedia/sets/72157633989397700/

What kind of money can one expect to make at your job?

Salary can range depending on your education level and where you are employed. The bottom 10% make $46k whereas the median salary for geologist in all sectors is $84k.

How do you move up in your field?

A geologist can advance their career by getting additional certifications (e.g. registered geologist) or pursue higher education. Specifically where I work, advancement of job positions [would be] into project management, such as technical team coordinator, team lead, or division director.

What advice would you give to those aspiring to join your profession?

The best advice I can give to an aspiring geologist is to never stop learning. Take as many science courses so can to figure out what field interests you, such as geology, engineering, physics, or mathematics. In addition, geography, computer science, environmental science, GIS, and drawing/art courses are also very helpful. Geology is a wide field with many hot topics to explore, including environmental or climate change, energy, geological hazards or mitigation, and mining. Examples of [jobs] in the field are engineering geologist, geochemist, geophysicist, hydrologist, mudlogger, wellsite geologist, environmental consultant, exploration geologist in academia, the oil, gas, petroleum sector, engineering or construction firms, government, museums, and private industry.

Vote for her LEGO set here: https://ideas.lego.com/projects/93813

I created the Research Geology LEGO set [because] I am also an active participant in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematic (STEM) education by being involved in high school career fairs and science activities. I feel that it is important to find fun ways to encourage children, of both genders, to use critical thinking skills. As an adult, I still play with LEGO, a cobblestone of my childhood. So I created a LEGO set called Research Geology, which highlights my career as a research geologist both in the field and in the laboratory. While I included both genders in my set, I wanted to highlight that women can be scientists too. I strongly believe that we can impact young minds and pave the way for future scientists. We can change the world, one geek at a time.

Missouri’s State Dinosaur

Photo by Serrator, https://www.flickr.com/photos/serrator/2333116195

Hypsibema missouriense is a type of dinosaur called a Hadrosaur or “duck-billed” dinosaur. It was a herbivore with jaws that contained over 1,000 teeth. Hypsibema had evolved specialized teeth to handle the tough, fibrous vegetation of the time. This dinosaur lived in Missouri during the Late Cretaceous Period. Hypsibema was first discovered in 1942 by Dan Stewart, near the town of Glen Allen, MO, and became the state’s official dinosaur on July 9, 2004 (RsMo 10.095) A reconstruction of Missouri’s State Dinosaur can be seen at the Bollinger Museum of Natural History in Marble Hill, MO. Source: Secretary of State webpage, http://sos.mo.gov/symbols/symbols.asp?symbol=dino

Missouri’s State Fossil

Photo by cobalt123, https://www.flickr.com/photos/cobalt/8461052030/in/photostream/

The crinoid became the state’s official fossil on June 16, 1989, after a group of Lee’s Summit school students worked through the legislative process to promote it as a state symbol. The crinoid (Delocrinus missouriensis) is a mineralization of an animal which, because of its plant-like appearance, was called the “sea lily.” Related to the starfish and sand dollar, the crinoid lived in the ocean that once covered Missouri. There are about 600 species alive in the ocean today. (RSMo 10.090) Source: http://sos.mo.gov/symbols/symbols.asp?symbol=fossil Note to people who live in Kansas: Kansas does not have an official state gem, mineral, rock, or fossil. If you would like to change this, you can contact one of your representatives and get one. I suggest Niobrara Chalk, as in Rock Chalk Jayhawks.

Trilobite Cookies

Stephen Greb, http://www.uky.edu/KGS/education/trilobitecookies2.htm

Even Easier Trilobite Cookies

by Stephen Greb, Kentucky Geological Survey

You’ll need:

1 bag of oval-shaped or circular cookies. Cookies that do not already have icing work best. Several types of cookies can be used, if you want to show variety.

1 cup of M & M’s ® (mini-size works well), Skittles ® or other small, round candies for eyes

Several tubes of icing for decorating. Large tubes and small, detail tubes can both be used.

Plastic knifes for spreading icing

Paper or plastic plates to make the cookies on

Paper towels for clean up

Preparation time: 15-30 minutes, depending on how many cookies you make

Recipe:

1. Place undecorated cookies on a plate or paper towel.

2. Decorate cookies using tube icing. Try to divide the cookies into three parts. You can spread icing on the top third and bottom third to model the head (cephalon) and tail (pygidium) of the trilobite. You can also divide the cookie into three parts along the long axis and spread icing on both sides, leaving the middle strip bare. This models the three longitudinal lobes of the trilobite. You can use small tube icing to make segments across the cookie, or bumps, or spines. Use your imagination.

3. Finish by placing two candy eyes on the head. You can use a dab of icing as “glue” to help hold the candy eyes down. If the eyes don’t stick, it’s okay; some trilobites lacked eyes and were blind.

4. Eat and enjoy!

Wisconsin Moonstone

When you think of rockhounding in Wisconsin, you probably think of Lake Superior agates. But did you know that Wisconsin also has moonstone? Read this article from the MWF January 2015 newsletter to find out more.

WISCONSIN’S MOONSTONE

by Dr. William S. Cordua

Emeritus professor of Geology

University of Wisconsin – River Falls

Imagine an October full moon in Wisconsin glowing ghostly blue to yellow as it seems to float over the newly harvested farm fields. Or is this captured in the rock? In Wisconsin’s own moonstone?

Wisconsin moonstone has been known for decades, but only recently have skilled lapidarists learned to work it to bring out its full beauty. This find surprises non-residents, who at generally associate Wisconsin gemstones with Lake Superior agates and nothing else. What is this material? How did it form? What causes its optical effect?

The moonstone localities are on private land in central Wisconsin, not far from Wausau in Marathon County. The mineral is a type of feldspar known as anorthoclase. This formed as a rock-forming mineral within the Wausau Igneous Complex, a series of plutons intruded between 1.52-1.48 billion years ago. There are at least 4 major intrusive pulses within the complex.

The anorthoclase is in the Stettin pluton, the earliest, least silicic and most alkalic of the plutons of the Wausau complex. This body is complexly zoned, largely circular in outcrop and has a diameter of about 4 miles. It is mostly made of syenite, an igneous rock resembling granite, but lower in silica and higher in alkali elements such as potassium and sodium. As such, it lacks quartz, but does contain a lot of alkali feldspar. Further complicating the geology is the intrusion of later pegmatite dikes. Some especially silica-poor varieties sport such odd minerals as nepheline, sodalite, fayalite, and sodium rich amphiboles and pyroxenes. Zircon, thorium, and various rare earth element minerals can be found in this pluton. Large prismatic crystals of arfvedsonite and nice green radiating groups of aegirine (acmite) crystals have been collected for years from these rocks. It is also the pegmatite dikes that contain the anorthoclase showing the moonstone effect.

The moonstone has been found in small pits and quarries and also in farm fields where masses weather out and get frost-heaved to the surface. The weathered masses of coarse cleavable feldspar may at first not look too interesting, but at the right angle the moonstone effect can be seen. The feldspar has two change and bounding capacity, so fit readily in the same niches in the feldspar. But sodium and potassium aren’t enough alike. If the feldspar cools down slowly, to below 400 degrees C, the feldspar structure contracts in size, and sodium and potassium are no longer good interchangeable fits. The homogenous anorthoclase splits on a fine scale into intergrown potassium feldspar and albite. Sometimes the bands of alternating minerals are coarse enough to see. Other times they are microscopic. If they are just the right size and spacing, they scatter the light that penetrates the various layers in the mineral – producing the moonstone effect, or schiller. The only anorthoclase that is truly not a mixture is that which cools very rapidly, such as in lava flows, so the separation cannot occur, and the mineral is frozen into its high temperature form. The material at Wausau cooled slowly, so isn’t, strictly speaking, anorthoclase anymore, but an exsolved mixture.

The crystalline structure controls the orientation of these exsolution bands, hence the effect is seen better on some surfaces (the {010} cleavage for example) than at others. This is one reason why shaping the rough stone takes such skill. Other challenges are the weathered nature of some of the stone, and exploiting the cleavage directions inherent in the feldspar.

The master of processing these stones is Bill Schoenfuss of Wausau, Wisconsin. Bill often exhibits and sells his beautifully prepared moonstone at shows in the upper midwest. He can be contacted at

Moonstone has been prized as a gem since antiquity, often characterized as being like solidified moonbeams. The Greeks and Romans both related the gem to their moon gods and goddesses. The American Gem Society considers moonstone an alternate birthstone for June.